|

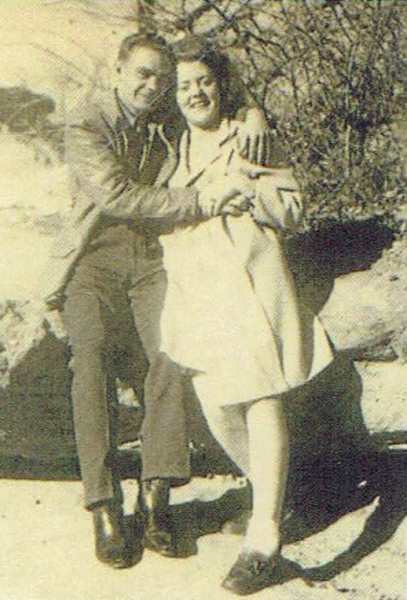

Austin married Faye Kinley in March 1946. They made their home in Texas and eventually had two daughters, Vicky and Judy. Austin lost the love of his life in September 2010.

|

Austin Steen Jr. of Crosbyton wanted to be a paratrooper. When World War II and age 18 came, he enlisted in the Army for basic training, then volunteered for duty in the paratroops and was assigned to the 17th Airborne Division, 513th Parachute Regiment.

Whether the prevailing factor in his choice was the prospect of high adventure, extra pay for jumps or the good looking boots paratroopers wore, Austin Steen went through the lengthy training it took. Then he was sent overseas in the latter half of 1944.

He had spent three months in England. Then they got their orders, one morning early after breakfast, to go into Belgium. It was the Battle of the Bulge.

The troops were flown over there and landed, as they decided the weather was too bad to jump.

"We rode those trucks until midnight, and stopped at a little town, spent the rest of the night and went on."

Ironically, German paratroopers had jumped that night, and one of Steen’s two Purple Heart Medals came for a wound inflicted between midnight and early morning before they left for Bastogne.

His group had entered a vacant building near the battle front and were stretched out on the floor asleep. Apparently, one of the German paratroopers entered the building silently, struck Steen above the right eye with a rifle butt in what was intended to be a lethal blow, then vanished into the night like he came.

"It was a glancing blow, and didn’t even knock me out. It busted up above my eye pretty good, and I still have a little scar up there," Steen said.

Despite the encounter, he doesn’t remember being especially nervous about approaching combat. “We didn’t really know what we were going into anyway.”

Steen carried a rifle and also was a message runner when communication with command was needed.

The fighting in and around Bastogne took about a month in snow that ranged from 12 to 18 inches: "We got most of our battalion knocked out there," he remembers.

His unit could dig foxholes in the frozen ground only with great difficulty. "It took some work to get a foxhole started, then you could go on down. We dug one every night, then would move somewhere else and dig another one."

He recalls, "The Germans were shelling us. What got most of our men was the German tanks. They were camouflaged-in pretty good, and we just walked flat into them. Didn’t see them until it was too late, saw them when they came out of the trees with the snow and started shelling us."

At that point, there was no advantage in digging foxholes. If you dug a foxhole, they would shell where you put dirt up on it. So you just had to lay in the snow.

"We got out of it pretty quick, ended up going further in to a little town behind the lines and came back out that night."

Steen doesn’t detail what the fighting — which took the lives of friends — looked and felt like, but after about a month there he spent the next month in a Normandy hospital with frozen feet.

"There was no cure for it. You just had to wait until ... if they turned black to your heels, they cut them off. And if the color went back, you got out."

Steen got out with his feet intact and a second Purple Heart Medal for injury in the war.

He said of the Battle of the Bulge that the German army was intent on breaking through the Allied lines.

"They came pretty close to making it. They had stacked up a lot of men and a lot of equipment for that. Actually, the gas was what stopped them more than anything, I guess — they ran out of gas in the tanks. Their plans were to siphon gas out of knocked-out equipment. Every German had a siphon hose with him. They would siphon gas out, and when they found out what they were doing, they began blowing up the equipment that already had been hit. That stopped them more than anything, I think. When they ran out of fuel, they just left their tanks and went back."

Steen did get his chance to parachute into combat before the main Allied crossing of the Rhine River. "We jumped across, and the British paratroops jumped with us."

Pontoon bridges were set up to allow the American infantry and the British infantry to cross, Steen said. "We lost a lot of friends there, and a lot in Bastogne. We lost 65 percent of our division when we jumped."

"We were scared. Everybody was."

He said, "They broke up the 17th — we got hit real bad on that jump. Instead of building it back, they said they didn’t need all of the divisions anymore, so they split us up. Part of us went into the 13th Division, the 7th, the 82nd and the 101st. I ended up in the 13th."